MODERN-DAY WOODCUTS

YANN LEGENDRE'S ILLUSTRATIONS FOR FORBES, GQ, The New York Times, and Wall Street Journal appear to be woodcuts fashioned from pixels. Thick, repeated lines create the illusion of motion with every strand of hair, every fold of cloth, and every shadow or reflection.

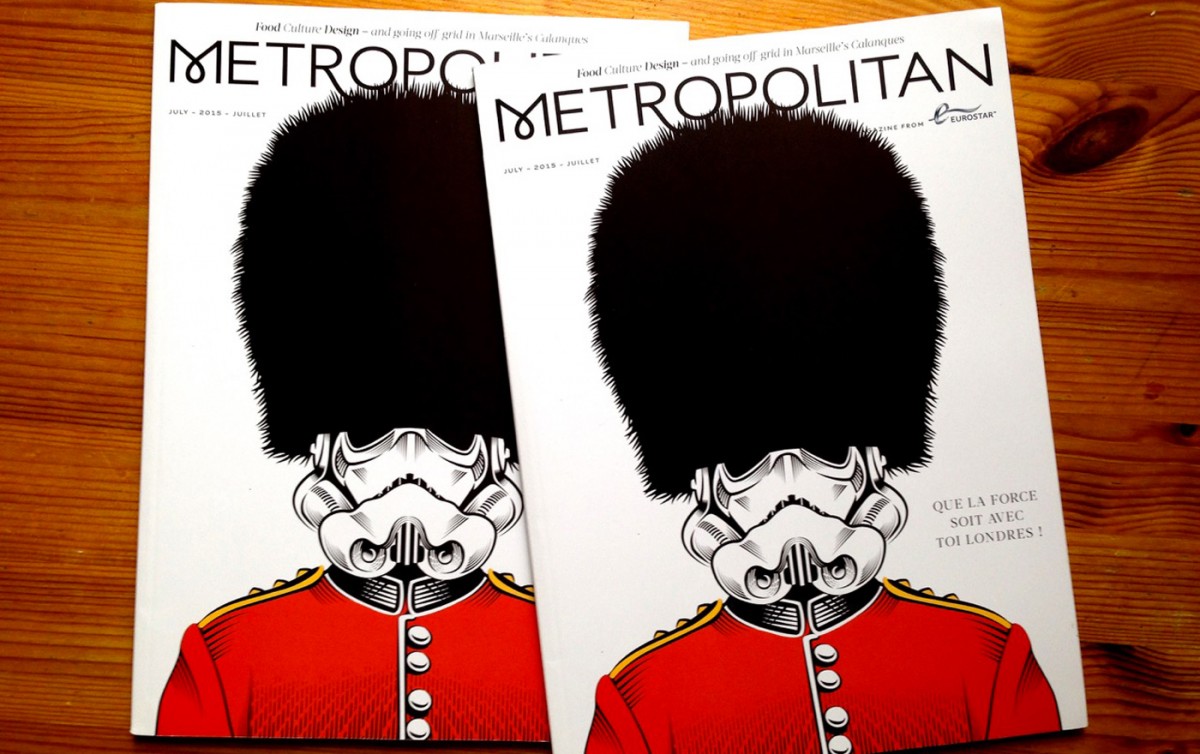

Even contemporary subjects have a timeless quality, whether it’s a portrait of a modern-day celebrity, a New York taxi, or a bearded hipster. And sometimes, the unexpected: A Stormtrooper wears a Beefeater’s hat, a pregnant woman poses seductively in lingerie, and Little Red Riding Hood appears even more devilish than her nemesis.

“Most of my education in art and illustration comes from my parents,” Legendre says in a thick French accent. “My father was an architect who also taught at an art school, and he designed our home, which felt like a space ship when I was growing up—a plastic house with big round windows; it was like something from another planet had landed in the middle of the forest.” That may explain why Legendre is able to mix classic, organic shapes with a modern aesthetic in a way that seems just right.

“Artists and famous creative famous people would visit for weeks at a time to work on paintings or sculptures, so I was surrounded by creativity.” Compared to those experiences, Legendre (pronounced le-ZHAN) found art school boring and narrow, and he couldn’t wait to escape. After graduating, he went to work at his father’s graphic design and architecture firm; a year later, he opened his own studio.

Legendre now splits his time between Bordeaux, in the south of France, and Chicago, where he’s closer to most of his editorial clients, and where he finds inspiration in American illustration. “If you’re looking to learn about art between the 14th century and 18th century, you go to France, but if you’re looking to learn about contemporary illustration, you go to the States,” he says. “In the 1950s and 1960s, everything exploded in the U.S., and I still find inspiration in book covers by Chip Kidd, in graphic novels, and American artwork—all of it.”

Legendre considers his biggest influences Picasso, M.C. Escher, and Jack Kirby, who teamed up with Stan Lee in the 1960s to create the Fantastic Four, X-Men, and the Hulk, before leaving for rival DC Comics. “Kirby’s work is so bold, almost like a nuclear attack exploding in your face,” says Legendre. “My style is a combination of that old-fashioned line work with a more contemporary tool.”

The signature style is clear in his work with Rockport Publishers, which yielded a new edition of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales in 2014.

“The Grimm stories were designed to be told, not read,” says Legendre. “The way they’re written is the way we talk, and because there’s so little detail, I can create the detail, and interpret the story through the illustration.”

Case in point: Little Red Riding Hood.

“In the story there is nothing saying that the girl is fragile or afraid of the wolf, so I didn’t want to illustrate her as a delicate little flower,” he says. Legendre drew her as a determined young woman with a hoodie—a character who appears to have just walked off the streets of New York, ready to face the evil hiding beneath her grandmother’s bedsheets.

ALL ABOUT THE PROCESS

Most illustrators spend time with pencil and paper, then scan their sketches, using digital tools to trace the work and polish it to perfection. Not Legendre.

“For me, the computer isn’t just a way to make something ‘clean’; it’s actually a tool for me to create,” he says. “There is no scale, so I can zoom into an illustration infinitely, and that allows me to make decisions that I couldn’t have thought of beforehand.”

He admits his use of Adobe Illustrator CC is rather simplistic. Relying primarily on brushes, the scroll pen, and the pencil tool and a curated library of line weights, he draws on the page just like an artist with a piece of paper, starting with black and white, and adding color later in the process. Legendre can get lost for hours while drawing individual strands of hair; rather than simply copying and pasting portions of illustrations, he created every “V” in film director Pedro Almodovar’s beard to ensure realism.

“When I’m creating a scene with a human character, I always start with the eyes, because they’re the only part of the body that’s the same size in everyone,” he says. “Then I move around the face, almost like a sculptor, exploring the rest of the page; when I start, I have no idea where I’m going to end.”

THE SEARCH FOR SURPRISE

Much of Legendre’s work is editorial, and he appreciates art directors who give him license to explore the subject rather than essentially creating a photograph of the story told in the article. “When an art director says, ‘We need some bright colors and something fun,’ that’s a brief I can handle.”

And because of that, Legendre rarely shows clients more than a simple collection of circles and squares indicating the composition; sometimes he prefers to completely surprise the art director.

“When Metropolitan Magazine asked for a cover illustration about Star Wars in London, it was easy—I immediately thought of the Stormtrooper with the guard’s hat and it was done,” Legendre says. “I showed the art director the final piece, and it was such a surprise!” he says, getting excited at the very memory of it. “But if I had created a sketch, it’s nothing—it’s just an idea that every illustrator could execute in a completely different way.” Legendre knows that completing a piece without a firm commitment from the client is a risky proposition, but to him, taking the risk is just part of the job; his client list reads like an airport newsstand, so it seems to be working out.

Given that heavy focus on editorial commissions, you might wonder if Legendre ever worries about the future of print.

“When I started working on illustrations for the New York Times in 2008, people were already saying the computer was going to be the end of print,” he says. “But really, the computer has just made my job easier—now I can work from anywhere I like.

“They also say nobody buys DVDs anymore, right? I work with Criterion Collection in New York, which is making a fortune selling DVDs because they create amazing objects—it’s an experience to open the box and look at the artwork before you watch the movie. Why? Because people are ready to spend money on a beautiful piece of craft.”

See more of Legendre’s work here.